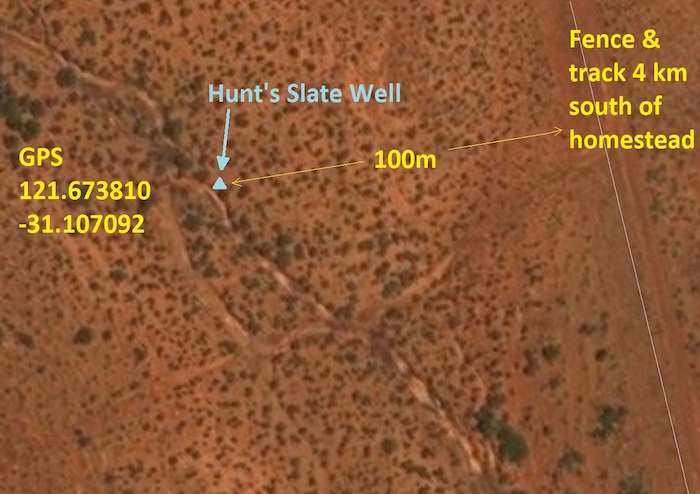

Location

GPS Coordinates

UTM

Zone 51J

373531 metres East

16557773 metres North

DMS

31°6'25.53"S

121° 40'25.73"E

DECIMAL DEGREES

-31.107092

121.673810

Directions

Condition

Hunt's Slate Well has been lost for 125 years. During a 90 day prospecting expedition with Gus Luck in 1894, David Carnegie recorded:

5 April 1894. Hunt’s Slate well where we looked upon getting water as a certainty. The original well dug by Hunt in /64 [actually 1866] has long since fallen in, but in the bed of a dry creek running thro’ an extensive (for this country) open plain, several holes have been sunk (to a depth of 10 or 12 feet) & water obtained.

History

Hunt’s Slate Well was uncovered in May 2022 after having been lost for more than 125 years.

This well was the most easterly of a series of wells created by Hunt’s team. It was the first physical development in the now City of Kalgoorlie-Boulder area.

The Hunt Track had huge significance to Western Australia’s heritage.

On June 1865 Hunt described in his journal that he had set the men to work sinking a well in a gully in a wide extent of flat. The ground was composed of layers of slate (schist which is a sedimentary rock) and it was hard work to get a hole down to blast. After four days work, sinking the well was discontinued at a depth of 4.7 metres without striking water and having used all the blasting powder. He wrote:

“In connection with the well, I have had the gully dug out to form a small tank at the 1st of rain both must become full of water, the tank being 40 feet long by 4 broad and 3 feet deep”.

Hunt called it Slate Well, however, it was later also called Slate Well Tank.

Hunt also constructed a tank about two kilometres further south that he called Slate Tank, which sometimes caused confusion between the two places. Hunt described Slate Tank as being formed by clearing out a deep clay hole in the bed of a gully and throwing up a strong embankment on the lower or southern side – length (35) feet - (10) broad and (5½) feet deep. Slate Tank does not appear to have survived to the 1890s gold rush.

Slate Well did survive but was fallen in and in poor condition. In November 1892 just two months after the discovery of gold at Coolgardie surveyor Noel Murray Brazier surveyed the track and wells noting:

“We were several days looking for Slate Well, which ultimately was found, completely surrounded by scrub, in the bed of a small creek flowing through a wide samphire flat into Lake Lefroy”.

The last record of people using Slate Well appears to be in 1897. The construction of a large tank at Wollubar in 1897 provided ample water for the area and it is likely that unreliable water sources such as Slate Well were bypassed and no longer maintained. Being in the bed of a creek Slate Well would have required regular removal of silt from floodwaters and a period of no maintenance resulted in it being completely covered.

In September 2021 the site was rediscovered by Eric Hancock and Peter Green after Eric’s research turned up a July 1893 ‘Yilgarn to Hampton Plains’ map showing all of the water supply points numbered commencing at H1 (Slate Well) following the track via Coolgardie, Gnarlbine and the Hunt Track back to Southern Cross. This map resulted from an expedition by surveyor Noel Murray Brazier in November-December 1892 immediately after the discovery of gold at Coolgardie.

Brazier’s survey field book showed that the well was about three metres north-north-west of a post he installed marked H1. With this background research, the search was primarily for the H1 surveyor’s post, rather than for the well in the bed of a creek that would be long covered over by silt and possibly changes to the creek location.

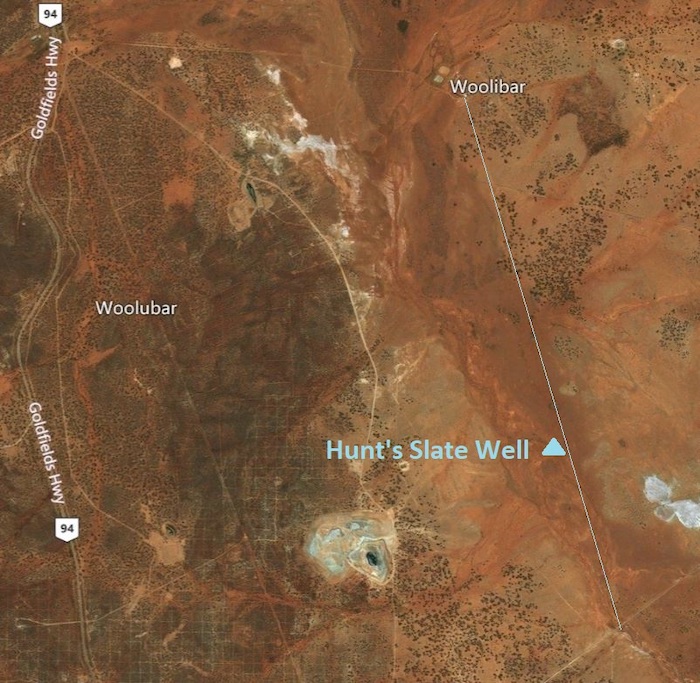

The site is on Woolibar Station about four kilometres south of the homestead. This is private property not generally open to the public, so any site visits require prior permission.

The 1892 H1 post is about four metres east of a north-south creek. The well was located where expected about 2.1 metres north-north-west of the H1 post.

Hunt did not strike water in the well and put a dam across the creek so it would backup and filtrate into the well.

Given that the well did not strike permanent water, was little used and by the early 1890s was partly collapsed and even by then hard to find, it is considered inadvisable to fully excavate the well.